Lap-See Lam & Charles Campbell at The Power Plant, Toronto

By Terence Dick

Early on in my tenure in a variety of roles at The Power Plant, I was told that the most popular attraction at Harbourfront Centre (which The PP is, as yet, part of) was the water (that is, Lake Ontario). It’s taken a quarter of a century, but the gallery has figured out that they have to fight fire with fire (or water with water), and currently has on display two artists in whose work the wettest of the elements plays a prominent part. Lap-See Lam’s video installation, Floating Sea Palace, presents an elliptical narrative of an endangered species of fish-people, while Charles Campbell’s hanging ceiling sculpture and wall works, how many colours has the sea, document the ocean depths and final breaths of those enslaved people who drowned in the Middle Passage.

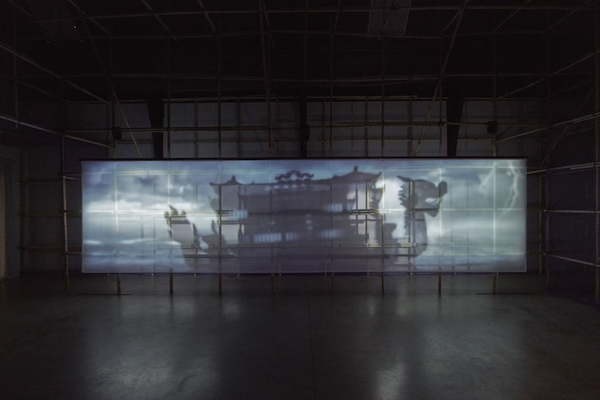

Lap-See Lam, Floating Sea Palace, 2024, installation view (photo: Andy Keate)

Floating Sea Palace transports the viewer to a place of myth by suspending its screen within a bamboo architecture that one must enter. Inside this darkened room with indistinct walls the video projection floats in the air, leaving its images porous and dreamlike. Lam, a Swedish-born artist whose family migrated to Europe from Hong Kong, dramatizes the folktale of Lo Ting, the last remaining half-human, half-fish member of a nearly extinct ancestral people, through a combination of live actors and shadowy animation.

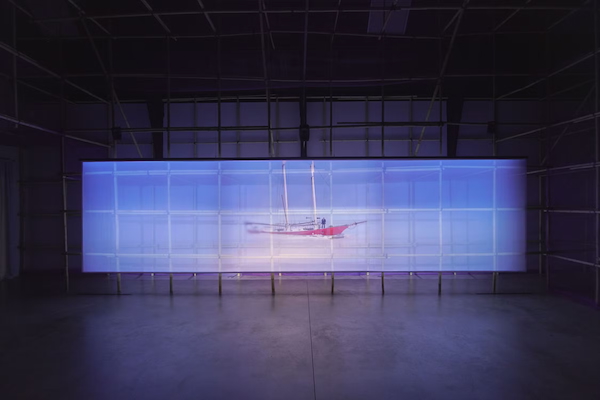

Lap-See Lam, Floating Sea Palace, 2024, installation view (photo: Andy Keate)

The beautifully shot video immerses the viewer, in the literal sense, in an undersea world of an idyllic past that is then destroyed by the greed of the surface-dwelling humans (basically, us). After Lo Ting’s people are hunted down and consumed, they remain as a single character split into past and future forms, which allows the latter to comment on the fate of the former. The parallels with our real life exploitation of the environment are clear, but themes of loss and mortality as well as migration and homelessness are woven throughout. The video ends with a haunting image of the narrator, Singing Chef, serenading us from an ice-bound dragon boat surrounded by the barren, white, frozen winter sea.

Charles Campbell, how many colours has the sea, 2024, installation view

Across the hall, Jamaican-born Canadian artist Charles Campbell applies conceptual devices to create visual analogues to the factual history of enslaved Africans being transported across the Atlantic Ocean to North American during the centuries of the slave trade. Hanging from the ceiling in the darkened gallery is an undulating grid of metal bars that map the geography of the submerged land where the two continents meet. It is both clinical and chilling in its evocation of data and disappearance, a digital graph of the burial ground of murdered Black men, women, and children.

Charles Campbell, how many colours has the sea, 2024, installation view

On the surrounding walls are colourful vertical strips or “breath portraits” that translate the exhalation of members of the Black community into abstract designs reminiscent of medical imagery or data displays. They are lit to glow in the murky exhibition space and evoke the final breaths of those who were killed. After the lyricism and fantasy of Floating Sea Palace, this installation is a stark reminder of the facts. Both artists have created elegies, though of contrasting tones. Lam’s speaks predominantly to the heart while Campbell’s speaks first to the mind. Together they imbue the landscape steps away from the gallery’s southern doors with the ghosts of our colonial past and the remaining guilt that still haunts us.

Lap-See Lam: Floating Sea Palace continues until March 2.

Charles Campbell: how many colours has the sea continues until March 2.

The Power Plant: https://www.thepowerplant.org/

The gallery is accessible.

Terence Dick is a freelance writer living in Toronto. He is the editor of Akimblog.