Christina Battle at Museum London

By Kim Neudorf

Christina Battle, Notes To Self, 2014 – ongoing, compilation of single channel videos with sound (courtesy of the artist)

In Notes to Self, the collection of single-channel videos that opens Christina Battle’s multimedia exhibition Under Metallic Skies, text-on-paper “notes” collected by the artist between 2014 and 2024 glow in the dark like miniature billboards at night. Lit afire by a torch or lighter, their oratory – which read as statements, social media commentary, poetic descriptors, and proclamations – has just enough to time to sink in before corners and edges burn, glow, curl, and turn to ash. The messages read as variously shocked, baffled, and exasperated reactions (“what the fuck is even happening right now?”) to situations of epic proportions, such as the ongoing climate crisis, the Covid-19 pandemic, and various wars and their aftermaths. At times expressing more abstract states of obliteration and being overwhelmed, the notes speak of past, present, and future “heavy times” while offering instructive tactics such as “look to the trees, they know where the water is” or “sometimes there’s power in staying under the radar.” The tone gradually shifts to the possibility of transformation and resistance in the face of impending destruction.

Christina Battle, seeds are meant to disperse, 2014 – ongoing, participatory project, zines, postcards (courtesy of the artist)

Envisioning collective resistance to the climate crisis is further explored through the shared planting of seeds in THE COMMUNITY IS NOT A HAPHAZARD COLLECTION OF INDIVIDUALS, a commissioned project first curated by the Synthetic Collective in 2021. This recent iteration is represented by a banner and map of Alberta, Ontario, and Quebec (provinces with the highest contamination from the plastics industry), as well as sample postcards from the project’s collaborative seed-planting action. Accompanying the postcards is information about “phytoremediation,” a process in which plants can help remove harmful substances from soil, water, and air. Via QR codes, gallery visitors can read more about phytoremediation and choose to participate, wherein they will receive seeds and helpful fungi to be planted in sites impacted by the petrochemical industry. The collaborative, world-shaping ability of planting seeds continues in seeds are meant to disperse. In two projected videos surrounded by close-up photographs of various seeds, text appears accompanied by layered images of insects, animals, various modern technologies, plants, and other natural phenomena. Memories of gardens are followed by associative thoughts on the word “doomsday,” seed vaults, seeds as currency, the extinction of pollinators such as bees, and planting seeds as a way to anticipate future weather.

Christina Battle, are we going to get blown off the planet (and what should we do about it), 2022, single-channel HD digital video, collaged fabric, wallpaper element designed by Anahì Gonzalez Teran and Shurui Wang (Collection of Museum London, Purchase, John H. and Elizabeth Moore Acquisition Fund, 2022)

Bad Stars, a multi-screen installation, considers the many ways in which we come to understand narratives of disaster through the often abstract nature of its associated representations. In are we going to get blown off the planet (and what should we do about it), a video installation originally shown in From Remote Stars: Buckminster Fuller, London, and Speculative Futures, curated by Kirsty Robertson and Sarah E.K. Smith in 2021, generic images of natural and technological forms amidst beach sunsets and geometric patterns are followed by messages such as “we are only able to tune in one millionth of reality” and “we have to really recognize that it isn’t normal.” In another video, the strangely ethereal tone of a reported “shooting” is heard against images of natural and human-made eruptions followed by insects, animals, and bucolic scenes. While references to comets, geysers, and cosmic anomalies are apt metaphors for disaster as “disruption…on a planetary scale,” both videos also suggest the way coverage of disasters is so often received through a visual aggregate of overstimulation and abstracted footage, flattening and obscuring specific effects, and repercussions experienced in real time.

Christina Battle, BAD STARS (detail), 2018, multi-screen installation (video loops, fabric prints)(courtesy of the artist)

In a large projection, a technological space resembling both Google Maps and early gaming technology becomes a futuristic present where the origins of disaster and collapse might be “pinned” and located. This digital space is in fact a map of Sarnia, ON, wherein effects of decades of pollution seem to have contributed to a living graveyard of environmental decay. In a narration by the artist, glimpses of Sarnia’s history of contamination (including that of the nearby community of the Aamjiwnaang First Nation or the Chippewas of Sarnia First Nation) are woven in between the “remote stars” of the cosmos and their ability to influence conceptions of disaster across the ages. Here, digital anomalies simultaneously architectural, geological, and biological float above similarly extraterrestrial buildings-as-trees-as-bones, echoing, as the narration suggests, “rare sightings of stone or metal objects thought to have fallen from the skies”.

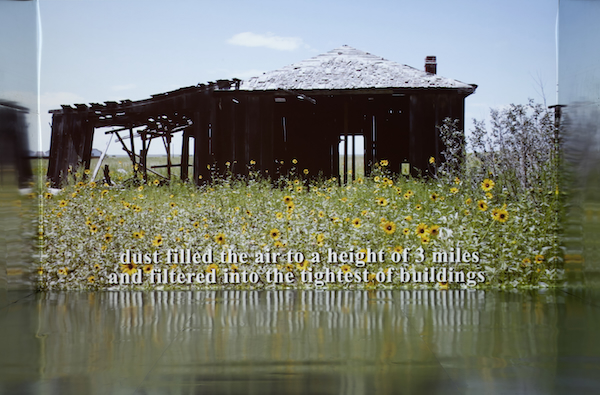

Christina Battle, dearfield, colorado, 2012, single-channel digital video, sound recording, metal, photograph (courtesy of the artist)

Remembering Through to the Future, a length of soft sculptures which spell out the work’s title, materially performs and is shaped by the layers of time and history involved in its making. Just as collecting seeds from plants chosen for their phytoremediation properties is affected by seasonal factors, processes of hand-dying, sewing, and cyanotyping fabric are similarly affected by the growth time of traditional plants used in natural dyes. Referencing Joyce Wieland’s 1960s textile work, Battle’s sculptures also make connections across time to histories of cultural, artistic, and activist handiwork. In proximity to this work is dearfield, colorado, a video installation which, through photographic archives, sound, and recent footage, explores another way to access the past through physical traces still resonant today. A photograph of a plaque gives context to the site of Dearfield, an African American settlement founded in 1910 with a community of 700 which, by 1940 post-Great Depression, fell drastically to twelve. In a large projection, present-day Dearfield appears as weathered, abandoned buildings surrounded by green fields of flowers. Overlaid throughout is text excerpted from archival accounts and scientific data describing how dust storms, such as that which once enveloped Dearfield, will electrify not only nearby surfaces but the very air (“fields sizzled under the metallic sky”). Insects, traffic, and birds can be heard as well as a low-vibration buzz, explained as “sferics” (electromagnetic impulses caused by dust storms and lightning). The video ends abruptly as a semi-truck zooms loudly across the screen, the image cutting to black before the distance is crossed – suggesting a buildup of tension never allowed to release. This buildup of energy, or “sizzle” of “metallic sky,” also referenced by Battle’s exhibition title, is given a final layer of affect via reflective surfaces fanning out from the left, right, and ground which surround the projection, mirroring and stretching the image as if hurtling towards and away from the screen. The suggestion is of a portal of time with a constantly moving center – cut short from any culmination or future, looped back on itself in perpetuity.

Christina Battle: Under Metallic Skies continues until November 3.

Museum London: https://museumlondon.ca/

The gallery is accessible.

Kim Neudorf is an artist and writer based in London (ON). Their writing and paintings have appeared most recently at Embassy Cultural House, London, ON; Support project space, London, ON; McIntosh Gallery, London, ON; DNA Gallery, London, ON; Paul Petro, Toronto; Franz Kaka, Toronto; Forest City Gallery, London, ON; Modern Fuel Artist-Run Centre, Kingston; Evans Contemporary Gallery, Peterborough; and Susan Hobbs Gallery, Toronto.