Jet Coghlan on The Red Rose Bleeds

Photo: Jae Yang

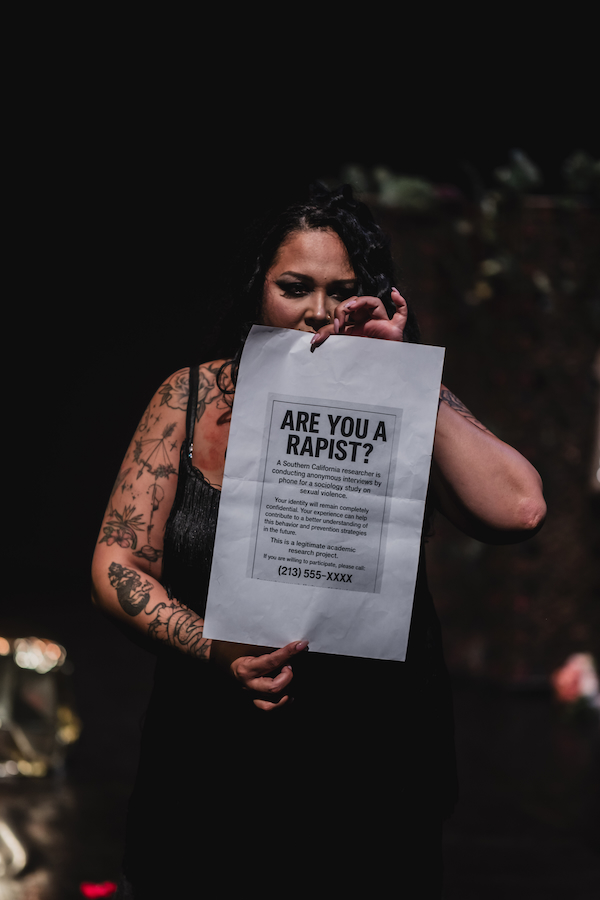

Performed at Theatre Passe Muraille in August as part of the SummerWorks Festival and produced by Phoenix the Fire, The Red Rose Bleeds unfolds as an unflinching exploration of rage, survival, and power. Written and performed by Gaitrie Persaud, the work fuses theatrical intensity and the use of American Sign Language (ASL), transforming the stage into both confession and confrontation. What begins as one woman’s story of survival evolves into a collective reckoning – an invitation for audiences to sit within the heat of vengeance, vulnerability, and truth.

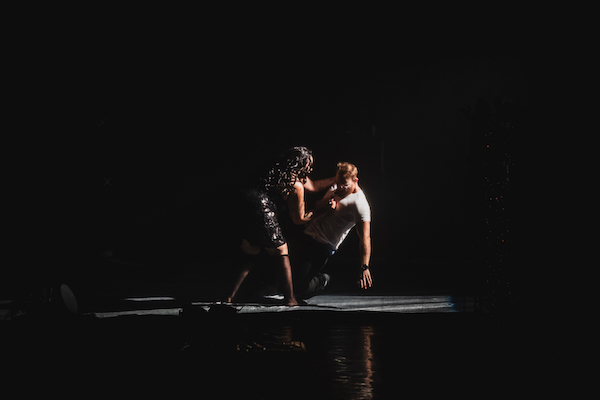

In the production, Persaud transforms the stage. “This is not just a story, it’s an exorcism,” she says. “It’s my way of confronting violence that society ignores, and giving voice to the silenced.” What emerges is a visceral and defiant performance where Deaf experience, trauma, and vengeance converge through light, American Sign Language, and embodied storytelling. Each gesture and flicker of light feels deliberate, as if language itself were being reborn through the body.

Photo: Jae Yang

Persaud describes the work as something that “began as my own way of surviving.” Over four years, she wrote and refined it, embracing it as “a healing process and a creative rebellion.” At its core is Enchante – a Deaf, female serial killer born from rage and resilience. “I shaped Enchante as a dark avenger – someone who does what the system fails to do. Like a Batman figure, but without mercy.” Through Enchante, Persaud channels a profound internal dialogue between justice and monstrosity, inviting the audience to question their own sense of morality.

In Enchante’s world, vengeance is not just catharsis; it’s reclamation. The “bad girl,” as she puts it, “is someone who refuses to be polite about her pain. She’s not interested in being palatable.” Through Enchante, Persaud reclaims what society often suppresses – female anger, Deaf identity, and survivorhood. “She fights back, even if it means breaking every rule. She is messy, complicated, and unapologetic.”

Photo: Jae Yang

The play foregrounds accessibility and audience participation in strikingly innovative ways. Created entirely in ASL before being interpreted for hearing audiences, Persaud describes this as “absolutely a ‘reverse access’ process.” Accessibility is not an accommodation here – it is the heartbeat of the work, shaping its rhythm, silences, and gestures from within. The performance also invites the audience to step closer, to cross the boundary between witness and world. During one sequence, audience members were invited to come forward and ask pre-recorded questions for Enchante, collapsing the distance between stage and spectator. The moment felt both intimate and disorienting, as if we had slipped into Enchante’s mindscape, which left me to wonder whether we were real, or only echoes of her imagination.

Persaud’s relationship to light is equally profound. “Because I’m Deaf, light is my first language on stage,” she notes. Lighting becomes emotional language: “gentle red glows for seduction, harsh flashes for violence, shadows for her inner darkness.” These choices heighten the visual rhythm of the performance, transforming each scene into a living canvas of rage and tenderness.

Photo: Jae Yang

Throughout, the performance pulses with the energy of confrontation and communion. One pivotal moment sees Enchante turn to the audience and confess she “could kill a few of them right now and mean it.” Persaud describes this as the moment she wants her audience to sit with: “That mix of fear, thrill, and complicity is exactly what I want them to wrestle with after the show.”

Behind the violence lies a deep emotional truth. “The joy is in owning the stage completely. It’s my story, my body, my language,” Persaud says. “The challenge is carrying that weight alone, especially when the material is so personal and triggering.” The result is a performance that refuses comfort, inviting audiences into the electric discomfort of survival and rage.

Photo: Jae Yang

In The Red Rose Bleeds, Deaf culture is not represented – it is embodied. “The storytelling began in ASL, in my body,” Persaud affirms. Through Enchante, Persaud commands both silence and space, redefining what power, access, and vengeance can look like when told through her eyes.

Jet Coghlan is an Autistic, Queer, Disabled, Mad researcher and performance artist, and the Digital Coordinator at Tangled Art + Disability.